A Tribute to Terrell Jones

October 25th, 1942 to August 15th, 2002

An earlier version of this story was first posted

to Light Morning’s website in the Autumn of 2002

Terrell Jones, a good friend and a fellow Vipassana meditator, died at his home just down the road from Light Morning in mid-August. Many of us in this area are indebted to Terrell, not only for introducing us to Vipassana meditation, but also for modeling an exceedingly rare quality — a learned ability to die well; to leave with awareness. As a small token of my appreciation, here are several stories about my Vipassana relationship with Terrell.

Noble Chatter

(Early 1994)

Terrell and I are walking through the woods, heading toward a small cabin on his and Diane’s land. He has just completed his first 10-day course at the Vipassana Meditation Center (V.M.C.) in Massachusetts. He called me as soon as he got home, wanting to share his experiences. So I rode my bike over. Terrell suggested that we talk at the cabin.

Walking beside him, I’m startled by the bounce in his step and the eager light in his eyes. Such a far cry from the listless, haunted, desperate friend of two weeks ago; a person so deeply mired in cravings and confusion that he was teetering on the edge of a precipice and about to lose everything that was dear to him: his health, his marriage, and his sanity.

Then a friend in Florida, who had taken only one course himself, had recommended Vipassana meditation.

“I’ll try anything,” Terrell had told me when he sent in his application.

We enter the cabin and sit down. For the next five hours, Terrell tells me about his course. In a ceaseless, effortless monologue, he describes the practice, recapitulates the teachings, enthuses about the center, and shares the insights he’d received. He says he now sees how self-centered and self-indulgent he had been.

“But this has changed my life, Robert. This has totally changed my life.”

When Terrell shows no signs of winding down, I start to wonder if his euphoria might be drug-induced. Did he ingest a little something when he got home? But when I share my suspicion with him, he laughs.

“No, no. That’s all behind me now. Besides, this is better than drugs.”

I will later learn that Terrell’s after-course eloquence is not uncommon. In the Vipassana tradition, students take a vow of silence when they begin a course. On Day 10, they’re released from this vow and Noble Silence gives way to noble chatter. All the pent-up feelings, experiences, and insights come tumbling out.

As our marathon session draws to a close, Terrell leans over and seizes my arm.

“You’ve got to take one of these courses, Robert. I just know it will be wonderful for you.”

“You’ve convinced me,” I reply. “You’ve come back from V.M.C. a new person. I want to see what you tapped into up there.”

Shut Up, Terrell

(December, 1995)

I’m slumped on a couch in Light Morning’s community shelter, staring into space, only distantly aware of Terrell talking to me from across the room. I’ve just returned from my first Vipassana course and I’m not feeling euphoric. Nor do I want to be talking with Terrell. Or anyone else.

More than a year had passed before my desire to sit a course at V.M.C. could be realized. Light Morning was finalizing the blueprints for a new shelter we would soon build. Then my wife Joyce decided that she was going to take a course. We didn’t want our 11-year-old daughter to be parent-less for two weeks, so we couldn’t go together.

Joyce went to V.M.C. with Terrell and Diane in June of 1995. When she came home, she started meditating two hours a day. My curiosity about Vipassana was further aroused.

Terrell and I made plans to sit a course together in September. But those plans had to be shelved when doctors discovered a melanoma behind one of his eyes. The tumor was successfully treated with laser surgery, but we couldn’t sit the course.

In December of 1995, another friend and I drove to Massachusetts and I sat my first 10-day course. It was traumatic. That’s why I’m sitting numbly on the couch, having what mental health professionals might call a nervous breakdown. And listening to Terrell gush about how great my course had been.

“Are you crazy?” I say. “Are you deaf? Didn’t I tell you what a rotten time I had? Didn’t you hear me say how much I hate Vipassana?”

“Yes, but how fortunate for you that such a big sankhara came up.”

I vaguely recall S.N. Goenka saying that sankharas are deeply rooted mental complexes. During the course, which is taught using Goenka’s audio instructions and video discourses, he also said that being deeply introverted for ten days can sometimes trigger these reactive energy knots, that can then be processed by the Vipassana practice and released. This is what Terrell is trying to convey. But I’m already too far down the rabbit hole.

“Shut up, Terrell.”

He smiles, tells me again what a great course I had, and leaves.

The Swish of the Horse’s Tail

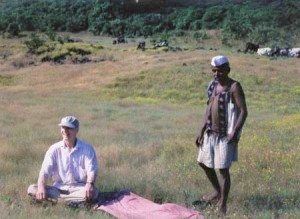

(June, 2002)

I’m visiting with Terrell while Diane is shopping in Roanoke. Terrell’s looking gaunt, but seems to be in good spirits. He shares an image he found in the teachings of Buddha: the swish of the horse’s tail.

A horse is grazing in a field. It’s tormented by pesky flies. The horse swishes its tail first one way and then the other. Back and forth, back and forth the tail goes — good times and bad times, pleasure and pain, hope and despair. Back and forth goes the swishing tail.

“Anicca [ah-KNEE-cha],” Terrell says with a smile.

Anicca is a word from the ancient Pali language that Gautama the Buddha spoke in 500 B.C. Goenka uses the word frequently during the 10-day course. Anicca is shorthand for the bedrock principle of impermanence; an experiential realization that everything is transitory; a visceral acceptance that this, too, shall pass.

Terrell and I joke about not wanting to look a gift horse in the mouth. Or in that other orifice of a horse’s anatomy to which its tail is attached. We also ruefully agree that gifts of the spirit can sometimes arrive in strange disguises.

Below the philosophical references and bantering humor, however, lies the poignancy of the present moment. Terrell’s looking gaunt because he’s probably dying of cancer. He’s also striving to die well, by putting the Vipassana teachings into practice.

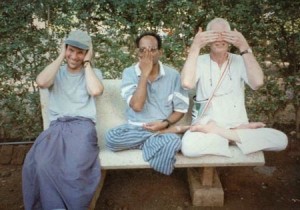

Hear no evil, speak no evil, see no evil.

Several months before the diagnosis, Joyce and I had gone to Terrell and Diane’s for supper. The four of us were making plans for a Vipassana course to be held in the Roanoke valley in late August. Terrell and Victoria, a Vipassana friend from New York, had been instrumental in bringing the intent for this course into focus.

But Terrell wasn’t looking good and he’d barely eaten anything. He had gone to see a doctor about his constant intestinal pain, but was sent home with the assurance that it was diverticulitis. Given Terrell’s prior history of melanoma, this was a tragic misdiagnosis.

In May, the four of us went to Charlotte, North Carolina, for a one-day course conducted by Goenka, who was traveling across North America on an extended tour called Meditation Now. Joyce and I sat the course, Terrell and Diane served it, and Victoria flew in from New York. We continued to plan the upcoming 10-day course in Roanoke.

Shortly after returning home from Charlotte, Terrell had finally been given the appropriate medical tests. The results showed that his melanoma from seven years ago had metastasized into his abdominal organs and couldn’t be treated.

Terrell and Diane were stunned, as was everyone else. Then our Vipassana practice kicked in. For years we had listened to Goenka say that one could die with awareness and equanimity. Vipassana is the art of dying, he said, and also the art of living. We learn to die smilingly by learning how to live smilingly.

That’s why Terrell and I are sitting in his living room, honing our awareness of the fleeting moment and joking about the swish of a horse’s tail. He’s reaching for a balance between trying to change his outward circumstances and accepting them.

“I’m keeping both sides open, Robert,” he says. “I’m going to pursue whatever experimental therapies I can. I know the odds aren’t so great, but there are spontaneous remissions. And I’m open to that. But I’m also open to this being my time to go. And if it is my time, I want to go well.”

I nod in agreement, feeling surprisingly at ease in the presence of my dying friend.

“Sadhu, Terrell. Sadhu,” I murmur softly to myself. “Well said, Terrell. Well said.”

The Miracle Pilgrimage

(Early August, 2002)

Joyce and I are once again visiting Terrell and Diane. They have just returned from a final journey to V.M.C. to see Goenka. And they’re radiantly happy. Listening to their stories, witnessing their bliss, I feel the unmistakable touch of the sacred, the numinous, the miraculous.

The pilgrimage was miraculous because it wasn’t looking like Terrell could even take that journey, let alone complete it. The past two weeks had been rough. The medications that softened the sharp edges of Terrell’s pain also rendered him less lucid during most of the day. Sometimes I would come over so that we could do our afternoon sits together. Terrell appreciated my presence, but couldn’t sustain his focus. It frustrated him.

“I only wish I could have another twenty years of practice to get ready for this,” he said. “But at least I have a practice. I don’t like to think about where I’d be right now without one.”

His words brought a smile of recollection to my face. Often, when people would ask Terrell about his Vipassana practice, he would reply by saying, “It’s the second hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life.”

This would reliably elicit the follow-up question that Terrell was waiting for: “So what’s the hardest thing you’ve ever done in your life?”

“The hardest thing I’ve ever done in my life was not doing Vipassana,” Terrell would say with a grin.

But now he was drifting further and further away. One time I even slept on a mat at the foot of his bed. I wasn’t sure he would make it through the night and I didn’t want Diane to be there alone with him when he died.

During his rare lucid intervals, Terrell would tell me how much he wanted to see Goenka one last time — to pay his respects; to convey the depth of his gratitude; and to simply be in his presence. Goenka would conclude his North American tour at V.M.C. in early August and spend a few days there before flying home to India. So Diane outfitted the back of their van with a comfortable mattress and prepared for the 12-hour drive to Massachusetts.

The journey, however, didn’t look promising. Even if Terrell survived the drive, would he know where he was when he got there? Or what he was there for?

Then Alta, an RN who was also a longtime friend and fellow Vipassana meditator, took a closer look at Terrell’s medications. She decided that the dosage he was taking was way too high. After consulting with his hospice physicians, she and Diane reduced his meds. The effects were dramatic. Terrell’s lucidity returned almost immediately. Now he could go on his pilgrimage.

And what a pilgrimage it had been. As Joyce and I listen to their excited tales, it becomes clear that the trip to V.M.C. not only went better than expected, it went better than they could have imagined.

Early August 2002

Mutual gratitude had flowed between Terrell and Goenka. Terrell was able to express his profound appreciation to his teacher. This had been the driving force behind the pilgrimage. But he wasn’t expecting the appreciation to be returned.

For Terrell had gifted Goenka with the opportunity to see one of his western students take the practice of Vipassana into the white hot heat of the final moments of his life, and to do so with a lighthearted, almost jovial equanimity. It was a striking affirmation that Goenka’s mission to bring Vipassana to the West — where few of his students were grounded in the Hindu/Buddhist belief in reincarnation — was bearing fruit.

“Look at this man,” Goenka said to a roomful of senior students and teachers at V.M.C. “He’s laughing and he’s dying. He’s dying and he’s laughing. This man understands my teachings.”

To Leave With Awareness

(Mid-August, 2002)

I’m meditating in a corner of Terrell’s bedroom in the middle of the night. Diane, Alta, and I are taking turns keeping vigil by his bedside. The end is near. Terrell is restless. He’s in and out of shallow sleep.

Suddenly he sits up, looks around, and sees me on my meditation cushion.

“Hi, Robert,” he says. “I didn’t know you were here.”

Terrell and I have had some good sharings over the past few days. We were able to resolve a concern he had about “the purity of my practice.” And he was enthusiastic about the special 10-day course I would be taking in the fall. Terrell also talked wistfully about the upcoming course in Roanoke, due to start in a few days. He had provided the impetus for that course. Now he won’t be able to see it through.

Other friends have stopped by for brief visits. All are touched by Diane and Terrell’s grace in the face of such challenging circumstances. It’s an eloquent testimony to their Vipassana training and daily practice.

Later in the night, Terrell awakens again.

“I’m dry as a bone, Robert. I’m dry as a bone.”

“You and the Earth both,” I think, as Terrell gets some chipped ice from a cup by his bed, sucks on it for a while, and then drifts back to sleep. The southeastern part of the country is in the grips of a prolonged drought. There’s been no rain for months and the land is desperately dry.

Daylight comes. Terrell has made it through one more night. I take a brief break to have breakfast with my Light Morning family, who I haven’t seen for days. Midway through breakfast, though, I get a phone call from Alta. Terrell has just died.

I drive back to find Diane and Alta quietly awed by the peacefulness of his passing. They tell me that just after I left, Terrell had awakened with anxiety.

“I know it’s time to go,” he said. “But I don’t know how.”

“Yes you do,” they said, each of them taking one of his hands. “Just be aware of your breathing. Follow your breath. You know how.”

So Terrell settled into anapana, the breath meditation technique that Vipassana students practice for the first third of each course. But after a short time, he lost his focus.

“I can’t do it,” he said.

“Yes you can!” Alta said. “You have to show us the way, Terrell. You’re our teacher here. You have to show us how to do this. We need to see how it’s done, so we’ll be able to do it, too.”

With that encouragement, Terrell was able to relax. He re-focused his awareness on his breathing, which became softer and softer, slower and slower. The out-breaths were slightly audible, like a quiet sigh or a soft chant. Slower and slower. Then he was gone.

By the time I return from Light Morning, Diane and Alta have bathed Terrell and dressed him in his special meditation clothes from India. I find him lying on his bed, perfectly still. No more pain, no more restlessness, no more anxiety.

I take a meditation cushion over to his bed and settle down beside him. As my stillness deepens, I feel the richness of our friendship; my gratitude to Terrell for introducing me to Vipassana; and for the priceless gift of a last sit together, here on his deathbed.

One more swish of the horse’s tail. Another poignant reminder of anicca. Another yielding to the implacable principle of impermanence.

As I sit meditating quietly beside Terrell, I start to hear rain. It’s soft at first, then becomes harder. Soon it’s beating down on the roof and soaking into the bone-dry Earth — a long, steady downpour.

“Thank you, Terrell,” I murmur. “Thank you for everything.”

Early August 2002

Epilogue

During Diane’s evening sit on the day Terrell died, the feeling came to her that in his final out-breaths (“slightly audible, like a quiet sigh or a soft chant”) Terrell had been Taking Refuge in the Triple Gem.

One of the formalities at the beginning of each Vipassana course (and Terrell had taken many) is to chant, in the ancient Pali language: “I take refuge in Buddha. I take refuge in dhamma. I take refuge in sangha.”

Buddham Saranam Gacchâmi.

Dhammam Saranam Gacchâmi.

Sangham Saranam Gacchâmi.

Taking refuge in Buddha — not in the person, but in the potential to be awakened and enlightened. Taking refuge in dhamma — in the law of nature and the practice of Vipassana. Taking refuge in sangha — in the fellowship of those who aim for wakefulness, and who practice accordingly.

* * *

The first 10-day Vipassana course in the Roanoke Valley, which Terrell helped to instigate and organize, was well attended and ran smoothly. Two more have been scheduled for late April and early September.

* * *

If you feel drawn to learn more about Vipassana meditation, as taught by S.N. Goenka, the home page for that tradition is here.

* * *

Terrell’s first Vipassana course dramatically changed his life for the better and

inspired me to sit a 10-day course in December of 1995. Twenty-five years later,

in December of 2020, I posted a three-part story of that course here.

It’s a story of trauma, catharsis, and synchronicity.

Thank you, Robert for sharing this. I was honored to share my life with Terrell. He was my husband, my mentor and my inspiration for everything I’ve done since his passing, to make my life more meaningful. Whenever I feel fear or uncertainty, Terrell’s words of wisdom and compassion flood my mind…and I’m at peace 💜

It was a blessing to have Terrell as a friend, Diane, and to keep vigil with him in his final hours. He introduced many of us to Vipassana and showed us that it’s possible to die well. He was a teacher who taught by example. Each time I go by your driveway, I think of both of you with warmth and appreciation.

Thank you for sharing this story of Terrell. I will especially remember S.N. Goenka’s words about Terrell, “He’s laughing and he’s dying. He’s dying and he’s laughing…” and the picture of his smiling, dying, very-alive face.

Yes, the closing photo tells the whole story. And how unusual, to have one’s death become such a gift.